(I initially published this text in Fifth Domain)

Any future nation-state adversary surely understands the U.S. reliance on satellite communications for global military operations. Therefore, they likely understand there is a crude and unsophisticated way to disturb and degrade satellite communication, an IED of outer space that can be introduced, by polluting orbits with shrapnel and debris that are likely to damage any space-borne assets in their way.

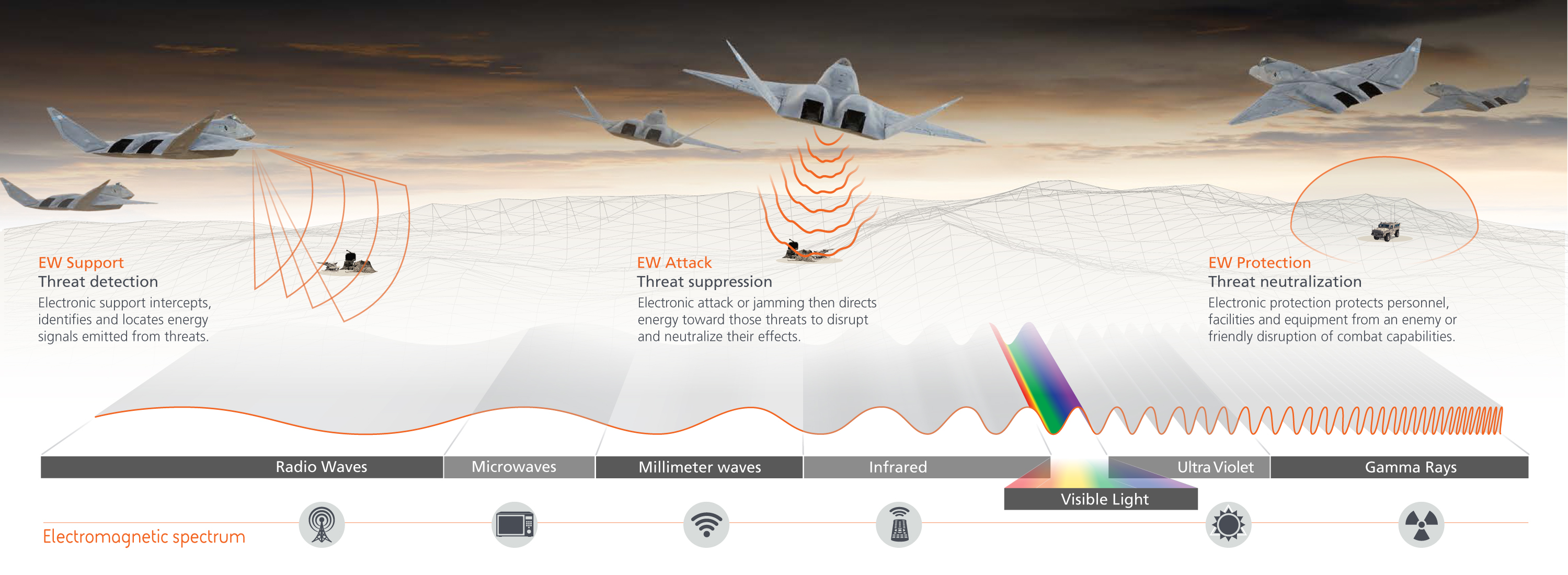

Essentially, an adversary can choose between two types of noncyber anti-satellite attacks: direct kinetic and indirect kinetic. While a direct kinetic anti-satellite missile attack on a U.S. satellite is possible, it would provide direct attribution to the attacker, thus leading to repercussions.

The thruster and the heat from a missile would be identified and attributed to the country or vessel that launched the attack. A direct kinetic attack might be inviting, but the political price is high. Even though it would be inviting to attack satellites, an adversary would not be able to attack without leaving a trace of tangible evidence. Using an ASAT missile is a grave act of war and can only reasonably be used if the perpetrator anticipates and accepts a wartime response.

For a potential adversary, it can be far more advantageous to increase the amount of debris that clutters specific orbits, thus epitomizing the indirect attack. Increasing debris can be accomplished through actively adding debris to specific well-targeted orbits, systematic designer accidents or collisions in space.

During the 18th century and until the Second World War, artillery units had a special round to be used if enemy infantry came uncomfortably close to the battery position: the case shot. The battery aimed toward the closing infantry and fired the case shots, which dispersed thousands of steel balls that created massive losses in the infantry ranks. Whether those steel balls hit an arm, a leg, the torso, or a hand did not matter; the infantry assault against the battery position lost momentum and ended.

By applying the case shot idea to space, we can see an unsophisticated way to radically increase debris by using space boosters to reach lower Earth orbit (LEO) and then using kinetic energy to disperse hundreds of thousands of shrapnel into a segment of space. Any obsolete or crude missile — exemplified by the Iranian Shahab or the North Korean Taepodong — could act as a space booster to take the payload to space. A salvo of 20 such crude space boosters delivering a significant amount of prefragmented shrapnel could radically increase the amount of hypervelocity debris.

The probability for collision in space between a functional satellite and debris is a numbers game. Reduced to a simplified example, if the presence of 5,000 debris pieces at a specific altitude generates a risk of one satellite hit every 10 years — not taking into account additional debris generated from the impact — an additional 100,000 debris pieces would increase that risk drastically.

To illustrate the principle, 20 space boosters can lift 30 metric tons of payload to LEO — roughly 300,000 10g steel balls — that would be spread at hypervelocity into the satellite orbits. The attack is kinetic but indirect, as the target satellites are not individually targeted but are instead approached by a swarm of hypervelocity debris that impacts the target satellites either by penetration or by destroying antennas, solar panels or other equipment. This impact would initially generate more debris, although orbital decay would counterbalance some of it by moving it to a lower altitude; eventually, it would disappear from space. It would serve as anti-access and area denial for defined space orbits, depending on the orbit, for a calculable amount of time.

Either a direct or indirect kinetic attack would be an act of war and provide the necessary attribution to give the United States casus belli approved by at least a part of the international community. First, both the direct and indirect kinetic attack would be attributable to the nation that launched the attack, and observations from space-borne monitoring satellites would be accurate enough to give the United States a solid case.

Second, creating unprecedented amounts of space debris would not only be hazardous to U.S. satellites, but also to those of other major powers. If rogue nation X launches an indirect kinetic attack, it could affect Russia, Europe, China, India, Pakistan and other nations’ satellites. Depending on the dispersing of these debris objects, damage could be limited to small areas of space, but it would still be a space territory not used solely by the United States. A future adversary will have to weigh the benefit against the geopolitical risk of collateral damage to friendly nations.

If the future adversary is ready to take the risk of collateral damage, it is likely within their reach to disrupt and degrade the satellites in targeted orbits or with reachable means, preventing the U.S. utilization of space terrain by using orbit pollution as area denial.

Jan Kallberg is a research scientist at the Army Cyber Institute at West Point and an assistant professor in the department of social sciences at the United States Military Academy. The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Army Cyber Institute at West Point, the United States Military Academy or the Department of Defense.