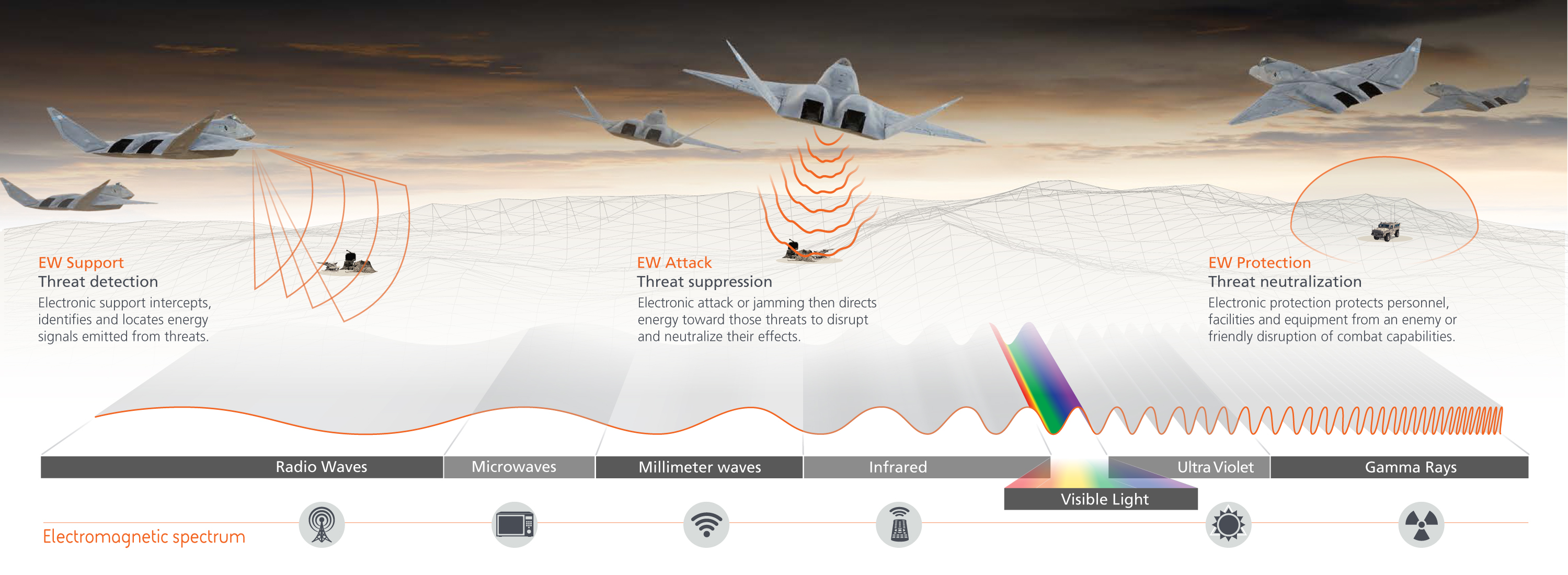

The Russian doctrine favors rapid employment of nonlethal effects, such as electronic warfare (EW), to paralyze and disrupt the enemy in the early hours of conflict. There was an expectation that a full-size Russian invasion of Ukraine would be a massive utilization of electronic warfare from the start.

In the afternoon on the first day of the Russian invasion, the 24th of February, it became apparent that the Russians faced significant command and coordination issues, as there was no effective electronic warfare against Ukrainian communications.

The rationale for the absence of Russian electronic warfare can have different origins; the Russians could have assumed marginal Ukrainian resistance and not deployed their EW capabilities. There was no tangible Russian EW engagement on day five of the invasion after stiff Ukrainian resistance. So if the Russian held back their EW early, the EW should be operational on day five, so the other explanation stands. The Russians can’t get their EW together.

In my view, that indicates that the Russians have failed to synchronize the EW, spectrum management, and the activities between different military formations to ensure functional, friendly communications; meanwhile, the Ukrainians are under Russian EW attack.

After this conflict, the Russian Ukrainian War, the Russians have learned from their failures and any potential adversary that studied the Russian Ukrainian War. The core problem of successfully doing EW is not the hardware; management and operational integration are the challenges.

Any potential adversary will adapt to the Russian Ukrainian War experience and focus on operational integration, but there is a risk for US status quo bias and unwillingness to invest in EW “because apparently, EW doesn’t work.”

The spurious assessment that EW doesn’t work and is not critical for the battlefield becomes the rationale for continuing the current marginal EW investment.

The last almost thirty years, American electronic warfare capabilities have been neglected because the spectrum was never contested in Iraq and Afghanistan. There was neither an enemy ability to detect and strike at electromagnetic activity, allowing for US command post radiating electromagnetic signatures and radiation from radios and data links with no risk of being annihilated when least expected.

During these decades, the other nations have incrementally and strategically increased their ability to conduct electronic warfare by denying and degrading spectrum and detecting electromagnetic activity leading to kinetic strike. Over the last years, the connection between electromagnetic radiation and kinetic strikes has been repeated along the frontlines in Donbas, where Russian-backed separatists shelled Ukrainian positions. In 2020, we witnessed it in the second Karabakh War Armenian command posts were located by their electromagnetic signature and rapidly knocked out in the early days of the war.

American forces are not prepared to face electronic warfare that is well-integrated and widely deployed in an opposing force.

For a potential future conflict, it is notable that the potential adversaries have heavily invested in the ability to conduct electronic warfare (EW) throughout their force structure. In the Russian Army, each motorized rifle regiment/brigade has an EW company, the division has an EW battalion, and within the Corps and Army structure, there are additional units to allocate to the direction of the thrust in the ground offensive. The Russians appear not to use it effectively, but they will learn and adapt.

At the doctrine level, the Russian ground forces are designed to be offensive and take the initiative from the first round is fired, where denial-of-spectrum access is a part of their strategy.

In theory, EW enables forward-maneuver battalions to engage and create disruption for the enemy and an opportunity for exploitation. The Russians benefit from decades of uninterrupted prioritization and development of EW, so they have the hardware, but it appears to be the integration that lacks.

Electronic warfare is a craft, a skill, and potential adversaries’ EW/signal officers are EW/signal officers their entire careers. Naturally, the potential adversaries’ junior and mid-career officers lack experience from the other Army branches and units, but they know the skills required in EW. In my view, it gives the potential adversaries’ an advantage in Electronic Warfare, compared to the US warrior-scholar that are shuttled around in a system of constant change of duty station, schools, and tasks.

The DOPMA “Defense Officer Personnel Management Act” has been discussed to undergo a significant revision, and it is essential to take into account the need for time and stability to gain craftmanship in EW, which is both technical and hands-on, which need officers to narrow down their specialization without career penalties or forced out of the force. The requirements for winning a war must prevail over a career flow chart driven by obsolete Taylorism and the belief that everyone is interchangeable. Not everyone is interchangeable, and uniquely talented leaders can ensure mission success through spectrum warfare. In the future fight, the EW units will have a far more active role and face constant targeting due to the EW units’ impact on the battlefield. This development requires leadership and decision-making by leaders who know EW craftmanship.

The Russian aggression in Ukraine is evidence that a more extensive ground war is possible. Our potential adversaries will learn and adapt their EW from the Russian Ukrainian war. Meanwhile, it is long overdue to accelerate the US investment in fielded and integrated EW. The current state of intermittent integration through formations and undersized EW capabilities compared to the battlefield needs has to change.

Every modern high-tech weapon system is a dud without access to the spectrum; that realization should be enough to address this issue.

Jan Kallberg

These opinions are my private viewpoints and do not reflect the position

of any employer.